|

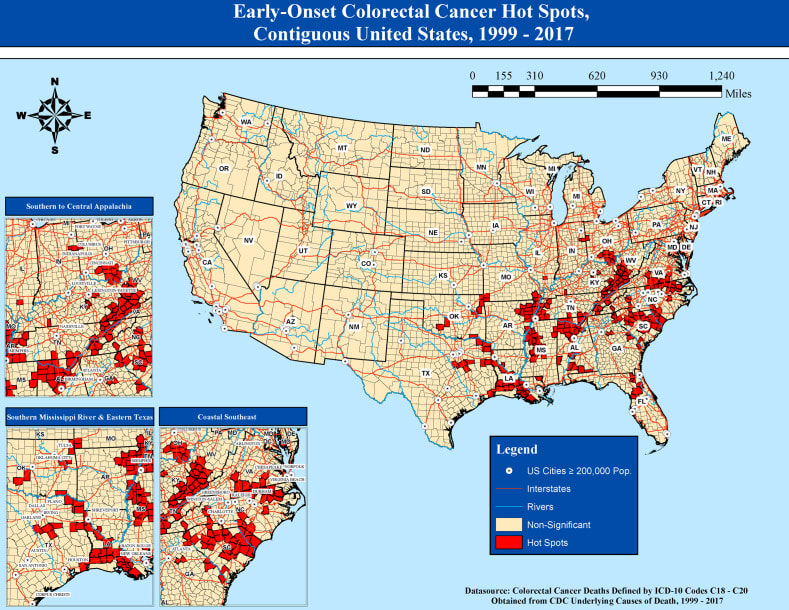

When the news dropped of Chadwick Boseman’s death at the age of 43, I, like so many others, was in complete shock. Such an amazing talent couldn’t be gone so soon, it just didn’t make any sense. He was a game-changing actor, rising at a seemingly unstoppable rate to great heights in his career. His role as “Black Panther” revolutionized the superhero movie genre and Chadwick himself came to embody unmatched strength, power, and courage. Little did we know that he was even more courageous than we could ever imagine, as he’d spent years privately battling colon cancer. Chadwick’s death rocked us to our core. Like the deaths of many of those who were taken seemingly before their time, it was almost impossible to wrap our heads around. He was just too young. For Black Millennials in particular, it was a sobering moment to contend with. Even in the face of other possible threats to our lives, we were forced like never before to come face to face with our own mortality. Because if the man who so convincingly embodied a superhero could be taken so soon by sickness, then we’re all fair game. The cold, hard truth is that colorectal cancer rates are rising among people of younger ages. While we’ve grown to understand colorectal cancer as something that hits people in their fifties, sixties, or older, more and more Millennials, who are currently in their thirties and forties, are experiencing an uptick in cases. While it still remains relatively rare, the rate of colorectal cancer in adults under 50 has doubled since 1990. Such an increase in such a short amount of time can’t be attributed to genetics, and is more than likely being caused by environmental factors such as poor diet, lack of exercise, smoking, and possible environmental toxicants. Boseman was born and raised in Anderson County, South Carolina, which is one of 232 counties in the United States that have been identified as a hotspot for early-onset colorectal cancer. The majority of these hotspots are located in the Southern U.S., with other counties located further up on the East coast. In these hotspots, survival rates are significantly worse among Black men. This also suggests that the root cause is environmental rather than genetic. This isn’t the only racial disparity that exists for Black people when it comes to colorectal cancer. Blacks are more likely to develop and die from colorectal cancer at a young age than Whites in general, and it may have a lot to do with the environments that we’re raised in. While the common refrain is that we simply don’t know what’s causing this uptick in cases, there’s a lot that is known that points to a necessary need for increased vigilance amongst Black Americans.

The Diet Switch Study In 2015, a study was conducted comparing the diets of African Americans with rural South Africans. While colon cancer is the second leading cause of cancer death among Western nations, it’s actually relatively rare among rural Africans. The study sought to find out if diet was the cause. The initial screening of the gut microbiome of both groups found biomarkers of increased cancer risk among the Black Americans, such as more polyps and higher levels of potentially pathogenic bacteria. In the guts of the rural Africans, signs of anti-inflammatory, anti-neoplastic (anti-tumor) byproducts of fiber fermentation were found. The diets of both groups were then switched, with the rural Africans eating a more Westernized, high-fat diet while the Americans ate the more high-fiber, low-fat diet of the rural Africans. Within just two weeks, the rural Africans developed colonic inflammation and signs of increased colon cancer risk. The Americans’ diet change showed a decrease of the biomarkers that indicated increased colon cancer risk. One biomarker, secondary bile salts, which is a known carcinogen, was reduced by 70% in the American group after switching to a rural African diet. For the rural Africans, their secondary bile salts shot up by 400% eating a typical Western diet. To put it simply, eating a rural African diet made the American guts healthier while eating a standard American diet gave the rural Africans an increased risk of developing disease. This one study illuminates what a lot of us already instinctively know. The high-fat, low-fiber Standard American Diet is damaging to our health, and drastically increases the risk of developing colon cancer. An earlier study in 1999 suggested that it isn’t simply the lack of fiber that explains the differences in colon cancer rates between Black Americans and rural Africans, but the presence of “aggressive” factors such as too much animal protein and high-fat meals, as well as differences in bacterial fermentation in the gut. Another study found that there is indeed a difference in the bacterial population in the guts of African Americans even when compared to Whites in the U.S. African Americans tend to have a higher population of Bilophila wadsworthia, an inflammatory bacteria linked to cancer growth. This type of bacteria proliferates when fed a diet high in fat and animal protein. The Right Way To Feed Yourself - And Your Gut Bacteria There are certain things we know when it comes to the development of colon cancer. Red and processed meats have been found in a number of studies to be linked to an increased risk of colon cancer. High intake of ultra-processed foods has also been linked to colon cancer, with smokers being especially susceptible. Being overweight or obese also increases the risk of developing colon cancer, especially for men and especially if the weight is gained starting in early adulthood. Taking everything into account, one thing becomes clear: how we eat matters. Eating a diet rich in red and processed meats as well as high fat foods while neglecting to eat fiber-rich, antioxidant-rich, anti-inflammatory foods on a regular basis sets us up for poor health outcomes and dramatically increases our risk of developing a number of life-threatening diseases, including colon cancer. When we eat, we aren’t simply feeding ourselves. We’re also feeding the trillions of tiny bacteria that live in our gut. There are many different kinds of gut bacteria, each of which thrive depending on the environment of our gut. The bacteria that imparts a protective effect on our health thrive on a variety of fiber-rich plant foods while the bacteria that promote inflammation and cancer growth thrive on high-fat foods. Unfortunately, the way we’ve been taught to eat creates a disease-causing environment in our gut. The good news is, if the diet switch study is any indication, our gut microbiome can change simply by changing our diets. Removing red, processed, and high-fat meats from the diet is the biggest change that you can make right now. Adding in beans, seeds, whole grains, and other forms of plant protein can help build up the populations of protective bacteria in your gut. Eat a variety of fruits and vegetables to reap the benefits of a multitude of health-promoting phytonutrients. Finally, get up and move! Your gut motility, the movement of food through your gut, is influenced by your body’s movement. This may be one reason why lack of physical activity is linked to increased colon cancer risk. The Need For Course Correction When I think of Millennials being diagnosed with and succumbing to colon cancer at a young age, I can’t help but think back to my childhood and teenage years. It was completely normal for my peers and I to eat processed meat on a daily basis in some form. Bacon, egg & cheese sandwiches, pepperoni pizzas, deli meat sandwiches, hot dogs, canned corned beef and vienna sausages were among the many high-fat, processed-meat based meals that I ate both at home and served to me at school. I definitely did not consume enough vegetables, fruits, beans, or whole grains, all of which contain nutrients that help to protect against disease. Imagine spending your most formative years, when your body is growing and developing, eating a diet full of foods that increase your risk of colon cancer and other chronic diseases. Imagine doing that for many years, from elementary school through high school, and beyond. After two or three decades, we’ve cultivated a gut that is ripe for disease. Even without smoking, even with leading an active lifestyle (which I personally didn’t), it would only be a matter of time before it all caught up. Let me be clear: we didn't choose this. We did not choose to be born into a society where our only nutrition education came from TV and billboard advertisements. We didn't choose to be born into communities without adequate access to fresh produce. We didn't choose to be born into neighborhoods overrun with fast food spots and liquor joints. We grew up in unhealthy environments shaped by forces beyond our control and quite often beyond the control of our parents. We grew to adopt eating habits and behaviors that served corporate interests without any real knowledge of just how much damage it was doing to our bodies. But now that we're old enough to make our own choices, we have to be honest with ourselves about the lifestyles we've come to embrace, even if they weren't our choices to begin with. We’re the hot dogs at every game, circus, or movie generation. We’re the meat lovers, pile it all on, stacks of processed meat on our pizza generation. We’re the bacon on every. damn. thing generation. We’re the cheese in the crust, cheese in every possible thing you can put it in generation. We’re the deep fry anything that can survive a vat of hot oil generation. We’re the watch TV, play video games, chill on our phone instead of going outside to play generation. We were raised on a lifestyle that has brought us here: a doubling in the rate of colon cancer over the course of a single generation - ours. Now that we’re aging, we’re seeing the effects of our younger years catching up to us. The good news is, there’s something that can be done about this. We just have to be willing to take an honest look at our lifestyles and have the courage to reject the unhealthy foods and habits that we were raised upon. Adopting a plant-based, active lifestyle changed my life and improved my health dramatically. While I may not know what the future brings or how much damage might have been done in the first couple decades of my life, I know that I can do what’s in my power now to ensure that I don’t keep making the same mistakes. For Black people, poor people, and those of us raised in food deserts and food swamps, a change in lifestyle is absolutely urgent. Colon cancer is just one of many preventable lifestyle-based diseases that plague our communities, taking away our loved ones well before their time. If the past year and a half has taught us anything, it’s that taking control of our health is absolutely paramount, even while we’re “young”.

0 Comments

Me at 16 years old. Me at 16 years old. When I was 16 years old, my mom hired me a personal trainer. It was at a gym that I'd never been to before, though I was no stranger to exercise. At the time I was quite overweight, and I'd tried in earnest to do the things that I thought would address the problem, but I honestly had no clue what to do. Though I was a bit apprehensive, I embraced the idea of having someone with the experience and expertise to help me along my journey. It turned out to be one of the most embarrassing experiences of my life. I don't think he liked me much. Why? To this day I'm unsure. I don't want to assume that it was because I was an overweight Black teenaged girl, but I don't think it helped that we had absolutely nothing in common. He was a muscular white guy, probably in his late twenties or early thirties, and considering that we were in a wealthier, majority white neighborhood that I did not live in, he probably hadn't had many clients like me. I was quiet and shy, but I did everything that was asked of me, without complaint. The workout would begin with a strength circuit, silently jumping from machine to machine. He'd adjust the weights and I'd perform the movements. Next he'd bring me over to the dreaded stairs where I'd have to run up and down for what seemed like ages. These were the moments when my lack of fitness really came to the fore. Those stairs would leave me winded and I'd always feel like a pathetic mess after the fact. Once it was all over, he'd plant me on one of the treadmills, tell me to walk for a half hour, then leave. No praise, no discussion of how I'm improving, nothing. The moment of embarrassment, the moment when I decided that I sure as hell would not be renewing my contract once it was over, came during a review of my diet journal. As was requested of me, I kept a detailed journal (as detailed as a 16 year old could anyway) of the meals I ate during the day and presented it to him for review. One day, I proudly handed over my diet journal, pleased with how many salads I'd managed to eat, confident that he'd see my efforts and be thrilled. Wrong. He blew up at me. Within view and earshot of other patrons, my trainer yelled at me and accused me of trying to sabotage myself. I was confused until he asked why the hell I would be eating a beef patty, so high in saturated fat, when I was trying to lose weight. Now, at 16, I had no clue what the hell saturated fat was or why I should be avoiding it. As a matter of fact, I'd never had any nutritional counseling or education whatsoever. It wasn't something that was taught in school, and it wasn't something that my trainer had discussed with me. All I knew was that I should "eat better", and so I ate as well as I knew how. I ate salads when possible, and smaller amounts of everything else. But being of Jamaican descent and living in a Jamaican neighborhood, beef patties were ubiquitous, and it felt like such a normal and harmless thing to eat. I figured, hell, it's high in protein, right? Never in my wildest dreams did I think that having one beef patty would be such a problem. I was humiliated. I felt smaller than I had already been feeling throughout the process, the smallest I'd felt since the entire thing started. I struggled, but I managed to hold back tears until our training session was over. For a few more weeks, I would continue to go to my training sessions, and the tension between us never dissipated. Once the training package had run its course, I told my mother to save her money because I would not be going back. I would continue to struggle with my weight and my diet for many years after this, putting on much more weight than when I began. I was no better off for having had a trainer, and in some ways, in the emotional and mental ways, the ways that I now know matter the most, I was worse off. My confidence was shot, and I felt like a hopeless cause. I've heard many similar stories since then. Stories of people shelling out their hard earned cash to pay for training packages with trainers who were rude, dismissive, judgmental, and racially or culturally insensitive. Trainers who resorted to verbal and emotional abuse instead of providing support. Trainers who put their clients through the motions of working out without explaining why they were doing the things that they were doing, only that they must do it if they want to reach their goals. This kind of training was popularized on television shows such as The Biggest Loser where overweight and obese contestants were regularly yelled at, belittled, and broken down under the guise of building them back up stronger. Their bodies were put on display in disturbing weigh-ins where normal, healthy weight loss was treated as failure while losing huge, unrealistic amounts of weight was celebrated as a success. We now know that the long-term result of all of this was metabolic damage, not to mention any emotional and psychological pain that was endured. Shows like The Biggest Loser perpetuate the notion that people who are overweight and obese deserve to be abused and humiliated. That they must pay penance for daring to exist in their fat bodies. While there are plenty of reasons why everyone should eat healthier and get regular exercise, abuse, belittlement and judgment are not the ways to go about it. After years and years of jumping from gym to gym and tinkering with my diet, I was finally able to lose a substantial amount of weight on my own. But I resented the fact that I had to go it alone. I had to do extensive amounts of research in order to successfully navigate the clusterfuck of nutrition and fitness misinformation that's out there. Now, with fitness training and nutrition coaching certifications under my belt, I see much more clearly just how fucked up my experience has been. It shouldn't be this hard. It shouldn't be this difficult to take control of your own body. It shouldn't be this hard to be healthy. But this is the environment that we live in. Decades of processed food products being normalized as daily fare. A fast food restaurant on just about every corner. Convenience foods sold as viable substitutes for home-cooked meals because if you want to pay your rent you have to spend obscene amounts of time working, and who has time and energy to cook after working 40+ hours a week? Public health messaging that tells you that if you just move more, you'll lose more, and everything will be fine. Diet companies that profit off of nutritional ignorance by promising you that their particular brand of trash or their proprietary method of starvation is exactly what you need to eat to lose weight. A government that's been co-opted by industry lobbyists who purposely obscure any attempt to tell you the truth - that eating their addictive products is making you fatter and unhealthier, and no amount of exercise in the world can offset a poor diet. As a nation, we don't know how to properly eat and it's by design. We keep pretending like we don't know how obesity rates continue to rise, but the answer is right there, plain as day: as the majority of working people toil day in and day out to afford a living, they're forced to prioritize financial survival over self-care, health and wellness, and billion-dollar industries - from food to fitness to pharmaceuticals - profit off of that fact. People are kept confused on purpose, and when they slip up and find themselves in a poor state of health, the entirety of the blame is placed squarely on their shoulders. It's their fault for being misled, for being misinformed, for being unaware. This is a cop-out that will continue to exacerbate the spiraling health conditions that we're experiencing as a nation. There are too many people suffering to continue to categorize this as simply a matter of individual willpower. Because the needs of industry are placed above the needs of the people, people are forced to be extra discerning about who to trust when it comes to nutrition and fitness advice. It is unfortunate that there seem to be more entities concerned about making a dollar than making a difference. One scroll through Instagram will show you countless examples of "professionals" who approach fitness from a place of vanity and showmanship, who are themselves equally as misinformed about health and nutrition as the people they're trying to take on as clients. People deserve better. They deserve to be seen as individuals, to be understood for who they are in the context of the lives they've lived and the experiences they've had, not as stereotypes. They deserve to have their needs and concerns addressed in a manner that is understanding and empathetic, not judgmental and dismissive. They deserve proper guidance on how to live a cohesive lifestyle where movement is accessible, enjoyable, desirable and safe, rather than painful and punishing. They deserve to be able to enjoy food confidently, knowing they've been armed with the knowledge necessary to make healthy decisions for themselves and their families. Unfortunately, I don't envision that the billion-dollar industries that profit from poor health will all of a sudden gain a conscience. Nor do I see our elected officials deciding to put their financial positions at stake by facing these industries head on. Change has to begin at the bottom. Until enough fitness and wellness professionals take it upon themselves to ensure that they're providing their clients with proper knowledge and treating them with the respect that they deserve, people will continue to fall prey to the well-established, insidious traps of diet and fitness fads. "Make sure you take a milk!" At lunch time, there was always a teacher's aide to remind us that our meals were not complete without one of the small boxes of milk piled up in huge bins at the end of the lunch line. Despite my former love affair with cheese I've always hated the taste of milk. The beverage that came in those little red & white boxes were absolutely disgusting to me and I did whatever I could to avoid having to drink it. When forced to, I would place a box of milk on my tray only to surreptitiously toss it in the nearest garbage bin once I was out of view of any nearby adults.

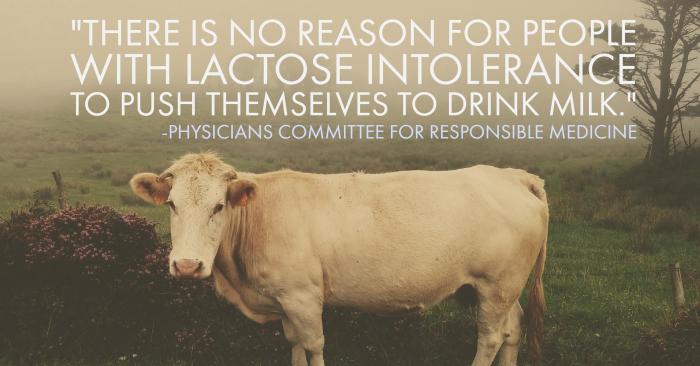

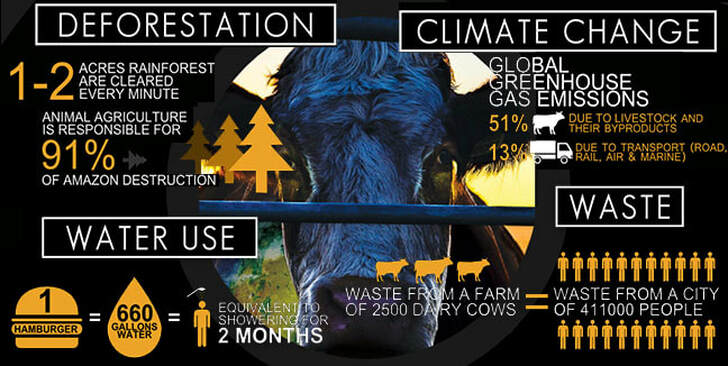

On luckier days, there would be some chocolate milk on hand. The sweet, chocolate flavor went a long way towards covering up the taste of the milk, and it was a whole lot easier to go down - or so I thought. Little did I know then that it was contributing to the near constant stomach aches, unbearable gas and frequent, unpleasant trips to the bathroom that I experienced as a child. My complaints were so frequent that my mom would schedule trips to the doctor's office, only to be told that they could find nothing wrong. I often wish that I'd had the luck of coming across a physician like Dr. Milton Mills, one with the knowledge and awareness to ask the questions necessary to diagnose what should have been fairly obvious: lactose intolerance. Instead, I made my way into adulthood continuing to consume dairy on a regular basis, though I'd long left my chocolate milk days behind. I was under the impression that dairy was a necessary part of my diet, providing nutrients like calcium and vitamin D that would supposedly build strong bones. As a child in public school, I was constantly being fed the message that I needed dairy. From the Got Milk? posters on the walls to those adamant lunch aides, countless authority figures in my life told me that dairy was a necessary and healthy part of my diet. But how can my body need something that clearly causes it harm? Lactase deficiency affects 60-80% of the Black population in America. This means that the majority of Black people in the United States do not possess the lactase enzyme necessary to properly digest dairy. Hispanic, Asian and Indigenous Americans also experience high rates of lactose intolerance and are unable to consume dairy without some sort of negative consequence. Thousands of Black children across America who are over-represented in high poverty public schools are depending upon their schools to provide breakfasts and lunches, as well as some general guidance regarding proper nutrition. The U.S. Dietary Guidelines is exactly where school administrators and policy makers turn to in order to formulate the menus for places like public schools. So why does the U.S. continue to push dairy as a necessary part of a healthy diet if a substantial portion of its population can't even digest it properly? One would hope that by now, given all the research available on the negative health effects of dairy, that these guidelines would be adjusted. Canada, for example, got rid of its 3 cups a day recommendation back in 2019, opting instead to group dairy in as a protein option. The U.S. Dietary Guidelines, however, continues to treat dairy as its own food group, recommending upwards of 3 cups of milk per day. One may respond that to their credit, the U.S. Dietary Guidelines have been updated to state that a comparably nutritious soy milk beverage may be substituted for cow's milk. But how does this translate into practice? The guidelines may allow for additional options, no doubt to save face, but what about cash-strapped public schools? I highly doubt that any of them can afford to provide an additional bin full of little boxes of soy milk for their lactose intolerant students. Not to mention that the MyPlate diagram, which is more public-facing and accessible than the 164-pg U.S. Dietary Guidelines document, continues to feature a cup simply marked "dairy". The diets of children aren't my only cause for concern. The guidelines continue to recommend 3 cups of milk per day into and throughout adulthood, despite research suggesting a link to various illnesses, including cancers. It has been found that women who consume even 1 cup of cow's milk per day had a 50% increase in their chances of breast cancer. This is particularly concerning for Black women, who die from breast cancer at rates 40% higher than their white counterparts. Black men are also disproportionately affected by illnesses linked to dairy consumption. A 2015 meta-analysis of 32 different studies found that dairy consumption increases risk of prostate cancer, and Black men have the highest rates of death from prostate cancer. The U.S. Dietary Guidelines stress that establishing healthy eating patterns in youth have a major effect of dietary patterns later in life. If such is the case, then it does a major disservice to Black children to insist that they must consume dairy, or to teach them that dairy is the only way to receive certain nutrients. Without a deliberate push to provide alternatives while making it clear that not consuming dairy is perfectly fine, the message received by most will be that dairy is a dietary necessity. I honestly call bullshit on the notion that the Guidelines were purely scientific and created with everyone's best interest in mind. If such were the case, then it wouldn't be so blatantly misleading. To present dairy as its own food group implies that dairy in and of itself contains nutrients that cannot be readily found elsewhere, which is patently false. It also does this while presenting paltry, insubstantial recommendations for other more nutritious foods. For example, while calcium can be readily found in green leafy vegetables, it is only recommended that they be consumed in quantities of 1.5 - 2 cups per week. Similarly, beans and legumes, which are also good calcium sources, are recommended at an intake of only 1-2 cups per week. This is compared to 3 cups of dairy per day, in spite of the fact that greens and beans provide exponentially more nutritional value than a cup of milk. I find it hard to believe that if lactose intolerance were not disproportionately suffered by Black people and other people of color that dairy would continue to be promoted as a recommended part of one's daily diet. It is difficult to ignore the contradictions and biases apparent in what should be a purely scientific and informational document, and it is difficult to ignore the racial disparities in poor health outcomes related to dairy consumption. Maybe if kale and lentils had powerful corporate lobbies behind them ensuring that their product was prioritized, promoted and subsidized with taxpayer dollars, the Guidelines might read quite differently. In what seems like a previous life, long before I committed to a plant-based diet and an ethical vegan lifestyle, I was in love with cheese. I mean desperately, obsessively in love with cheese. However, this was a totally one-sided love affair because one thing was for certain: cheese did not love me. It all started, as so many problems do, during my childhood. My mother used to host art shows in our home, which was always exciting for me not only because I'm an artist at heart, but because this always meant that there would be a table full of hors d'oeuvres. Being that I was only a kid, it was easy to hang around the hors d'oeuvres table, picking at food without judgment while the adults oohed and aahed over gorgeous Black art. I took full advantage of their collective distraction and zeroed in on what I really wanted: cheese. You know the stuff, the solid blocks of cheddar and pepper jack that come wrapped in shiny metallic wrappers. My mother would cut them up into bite-sized little cubes and lay them out next to some tasty crackers. I had no interest in the crackers, however. It was the cheese that I'd come for. I'd stand there, popping cube after delicious cube of cheese into my mouth, damn near melting into ecstasy under the snack table. I really wasn't concerned whether or not the guests had gotten their share. As far as I was concerned, Christmas had come early, and the cheese was all mine. This marked the beginning of a years-long habit. As a kid, I'd run to the fridge to munch on individually wrapped slices of American cheese. In elementary and middle school, I chose whatever cheese option they had for the day, whether it be pizza or a cheeseburger, or an ooey gooey grilled cheese. Our after school hangout spot was the nearby pizza shop. During high school, I'd spend what little money I had to engage in my morning ritual of scarfing down beloved New York classics like bacon, egg & cheese sandwiches (with salt, pepper & ketchup!), or bagels with thick, obscene layers of cream cheese. This diet followed me right into college where, with my newfound freedom, I ate whatever cheesy thing was available in the Morningside Heights neighborhood where I was located - and there were endless options. It wasn't until I was in the middle of my twenties that I realized that I'd long been exhibiting gastrointestinal symptoms as a result of my cheese habit. I mean, there were signs. There had always been signs - I just refused to see them. Once during my preteen years I was at a family party hanging out with my cousins, eating ice cream and enjoying various childhood shenanigans. To my embarrassment, I accidentally let one rip, engulfing the room in an odor that had my cousins scattering away in shock. "Nivea! You're lactose intolerant! You need to stop eating all that ice cream!", my cousin yelled at me. Now, as far as I was concerned, she was no medical doctor and I'd never received such a diagnosis so she could kick rocks. There was no way in hell that I was going to give up dairy - or so I thought. As the years went by it became obvious that dairy wasn't doing my body good. I'd long suffered from regular bouts of diarrhea and terrible gas, but it took forever to make the link to dairy. There was no way that something so delicious was doing me any harm. I refused to believe it. Throughout college I kept a Costco-sized box of Lactaid nearby to pop whenever I wanted to indulge in some cheesy goodness. This worked, but only for a while. Eventually it felt like I needed more and more of it for it to work. But it was a Costco-sized box so, I always had plenty. Then, a couple years after I'd left college, I was eating a protein bar after a workout when I suddenly experienced itching in the back of my throat. This itchiness spread slowly throughout my body. I was having an allergic reaction. That was when I learned that I'd somehow developed an allergy to whey, a protein found in milk. Now, this did not bode well for my cheese addiction. After hitting up Google, I learned that some aged cheeses were very low in whey, so maybe I could still eat it, as long as I stuck to those few. This was a short-lived revelation, however, as my stomach problems had gotten so bad that I couldn't deny it anymore: my beloved cheese was hurting me. I had to give it up for good. It wasn't until I began this current plant-based journey that I realized I'd been harming myself all along. I learned that because cow's milk comes from lactating cows, it is high in mammalian estrogen that our body does not distinguish from our own. It's no wonder that I suffered from debilitating menstrual periods every month. I also learned that upwards of 70-75% of people of African descent (and high percentages of other people of color) are genetically lactose intolerant. Though it took over a decade to admit it, my cousin was right after all. My body could not digest lactose, and it had been openly rejecting it since childhood. So why was it so hard to give up? Despite countless hours spent glued to the toilet in agony, I refused to believe that dairy was the problem. After all, I'd learned growing up that dairy was a necessary food group and that I'd be deficient in calcium if I didn't consume it. Things weren't adding up. Why would the authorities that I presumed had my health in mind recommend that I consume something that was making me sick? It was also cheap as hell and readily available virtually everywhere in my neighborhood. I eventually learned that this was not by coincidence but by design. Our government subsidizes dairy via the dairy checkoff program in order to promote the sale and consumption of dairy that is produced in excess. In the case of places like the Bronx where I grew up, cheese is easy to access for very little cost, which is why it is found in ample amounts in virtually everything - from fast food to school food to bodega food. This is despite the fact that a significant portion of those of us who live here cannot digest lactose and should not be consuming it. Cheese was also extremely hard for me to give up because of its chemical composition. Cheese contains an opiate-like compound called casomorphin. Its natural purpose is to make a mother cow's milk enjoyable enough to the calf that it keeps coming back for more. The problem is that it makes dairy addictive to humans, as well. It also contains growth hormones which are great for growing a baby calf into a full-grown cow, but which wreak havoc in human bodies, promoting the growth of things like excess adipose tissue and tumors. Honestly, looking back, I'm thankful for the signals that my body was giving me, even if it took way too long for me heed the warning signs. Politics, money and systemic racism are the true drivers behind the blanket recommendations to consume dairy - not science. Had I continued to listen to dietary guidelines rather than my body, I'd still be battling with the myriad symptoms that came from consuming something that my body was never meant to consume. From acne to painful periods to other menstrual disorders and hormone-driven breast, ovarian and prostate cancers, dairy has been widely linked to health problems. Dairy broke up with me long before I was ready to let go, and honestly, I'm glad it did. I'll get my calcium from kale, thank you very much. When I first adopted a vegan lifestyle in April 2017, it was the beginning of an exciting, illuminating and sobering journey that I've come to fall deeply in love with. Suddenly, my entire world view had been flipped upside-down. Everything I thought I knew about food, nutrition and health was revealed to be false, meaning that much of what I'd been taught throughout my life was completely untrue. It was daunting to realize that I knew so little and had so much to learn, but I was ready. Because of my personal health struggles, I was fully prepared to re-learn everything I thought I knew about healthy eating and living a holistically healthy lifestyle. What I didn't expect was that my veganism would grow beyond my motivation to live a healthy lifestyle. While I'd always been quite sensitive to social injustices, going vegan made it abundantly clear to me that the way I lived previously contradicted my desire to live in an equitable and just world. I became aware of the multitude of abuses that arise from our agriculture system, and as the information mounted, the more I realized that veganism was about more than the simple act of eliminating meat and dairy from my diet. For the first time I made the connection between the food choices I made several times a day, and various forms of social injustice and destruction. Prior to going vegan, I spent about three years of my life as a pescetarian, not considering the fact that within my lifetime we're likely to witness fishless oceans. It simply didn't dawn on me that every time I ate seafood, I was contributing to a demand for fish that is currently depleting life from our oceans. In all the years that I ate meat, I never once considered the abuse, pain, torture and utter turmoil that exists within these massive slaughterhouses that produce our meat. It wasn't until I challenged myself to watch videos and look - really look - at the pain from which my food was produced that I was fully and utterly turned off from the notion of consuming meat. It was through veganism that I learned that my natural inclination for empathy also extends to non-human beings. I was finally humbled enough to question the notion of human dominance. For the first time, I saw non-domesticated animals as sentient and just as deserving of life as I am. After watching What The Health, I learned about the horrific health consequences facing poor people of color who live near large-scale industrial animal farms. To make it worse, these health consequences aren't limited to nearby residents or poor, overworked farm workers. Large-scale animal agriculture is also responsible for polluting our air, our water, and our crops. Indeed, we can point directly to animal agriculture as a major contributor to climate change. Without question, the world's appetite for meat is literally making our planet sick. But it's also making us sick, too. My original motivation for going vegan - my health - never wavered, and while I educated myself about veganism as a lifestyle, I also delved into the nutritional aspects. I started watching lectures and reading books, gathering knowledge from doctors, scientists and holistic healers alike. From T. Colin Campbell to Dr. Greger to Karyn Calabrese to Chef Akhi to Dr. Sebi and more, the idea that gaining health comes from eating plant foods in their most whole, unadulterated form became a common theme. It's been almost 2 years since I've changed my diet and every day I marvel at how much my health has improved and continues to improve in ways that I never imagined possible. The opposite is also true, however. Not eating whole fruits, vegetables, grains, legumes, seeds and herbs contributes greatly to poor health. With enough research it becomes painfully obvious that diet is the most crucial factor when it comes to cultivating and maintaining optimal health. Most of the chronic diseases that are negatively impacting and ultimately claiming the lives of our friends, families, coworkers and acquaintances can be traced back to poor dietary choices. (Please, if you can, make time to watch the lecture above, it's worth it.)

I've come to realize that there is a schism that exists within the vegan community, with die-hard vegan-for-the-animals folk clashing with self-described plant-based folk. While one side ignores the notion that diet and health are intricately connected, the other side neglects to consider the greater humanitarian value of making the right food choices. From my own experience thus far, the two concepts are inextricably linked. As an individual concerned about my health, my choices matter. As a human sharing this planet with other beings, my choices matter. As a person concerned about the welfare of future generations as well as the future of the planet we live on, my choices matter. I embrace the vegan label just as wholeheartedly as I commit to a whole food, plant-based diet because I care about the health of the world as much as I care about my own personal health. It is of very little benefit to me to be healthy in an ill world. Indeed, I can only ever be as healthy as the world that I live in and the people who inhabit it with me. As much as we may want to pretend that we are all islands, we aren't. What we do (or don't do) affects our planet and its inhabitants, just as surely as we as individuals are affected by the health of our planet and fellow citizens. Our collective choices matter, and we're slowly but surely being forced to face that fact. Whether it be mounting collective medical debt, poor air quality, impotable water, dying oceans, or any of the major crises that currently exist, those of us who are able are going to have to take up the mantle. For the sake of ourselves, for our loved ones, for the poor, the innocent, the disenfranchised, and for all the generations to come, we must make more responsible choices. And it all begins on our plates. |

AuthorMy name is Nivea, but you can call me Niv. I'm an independent Plant-Based Nutrition & Fitness Coach hailing from the Bronx, NY. Archives

August 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed